Script error: No such module "Wp/dtp/Other uses".

Zigurat (/ˈzɪɡʊˌræt/; Cuneiform: 𒅆𒂍𒉪, Akkadian: ziqqurratum,[2] D-stem of zaqārum 'montok popokito, montok popoingkawas',[3] serumpun miampai do boros Semitik suai miagal do Hebrew zaqar (זָקַר) 'popokito'[4][5]) nopo nga' iso kawo struktur winonsoi di agayo id Mesapotamia kuno. Iti nopo nga' kibontuk do sebatian kitingkat do mogisusuhut id monikid tingkat toi ko' taang. Zigurat di okito kopio nopo nga' kohompit no Great Ziggurat of Ur id somok do Nasiriyah, Ziggurat of Aqar Quf somok do Baghdad, nohias no dinondo Etemenanki id Babylon, Chogha Zanbil id Khūzestān om Sialk. Otumbayaan o Sumerian do poingion o kinorohingan id sawat do kuil dii, mantad di, imam om soosongulun di bobos pantangon di suai no milo sumuang id kinoyonon dii. Tongotulun Sumeria diti nopo nga' manahak do tulun diti do tutungkap miagal do tuunion, asil pomutanaman om nogi tinunturu patung sambayangan montok mamagayat diolo mion id kuil dii.

Sajara

Hogot zigurat nopo diti nga' naanu mantad ziqqurratum (kinawas, timpak), id Assyria kuno. Mantad zaqārum, montok maan poingkawaso. Ziggurat of Ur nopo nga' zigurat Neo-Sumerian winonsoi di Raja Ur-Nammu, montok patahakon kumaa di Nanna/Sîn sabaagi tanda do kapamantangan kiikiro do abad ko-21 BC maamaso do Third Dynasty of Ur.[6]

Kotolinahasan

Winonsoi do Sumerian kuno Akkadian, Elamites, Eblaite, and Babylonian o Zigurat montok kotumbayaan sandad. Monikid zigurat nopo nga' soboogian mantad do kuil kompleks i kohompit do winonsoi suai. I minongimpuun do zigurat nopo nga' pinopoinsawat platform maamaso timpu mantad do timpu Ubaid[7] maamaso do millennium koonom Sobolum Masihi. Zigurat nopo nga' nokotimpuun sabaagi platform (koubasan nopo nga' oval, apat pasagi toi ko' apat pasagi miagal). Zigurat nopo nga' mastaba struktur miampai sawat di apatau. Bata di pinokoring momoguno tadau nopo nga' winonsoi sabaagi teras do zigurat om pinotoguang o bata diti id soliwan. Monikid laang nopo nga' sorokookoro mantad do laang id siriba dii. Kotoguangon nopo diri nga koubasan no kikaca di mogisuusuai warana om haro astrologikal signifikan. Kadang-kadang, haro ngaran do raja diti pinosuat id bata kikaca diti. Numbur do tingkat nopo nga' nulud mantad duo gisom turu.

Tumanud do puru arkeologi Harriet Crawford, Template:Wp/dtp/Blockquote

Akses kumaa kuil nopo nga' kosiliu do iso siri tanjakan montok iso boogian do zigurat toi ko' tanjakan lingkaran mantad kotimpuunon gisom timpak. Zigurat Mesapotamian nopo nga' okon ko' kinoyonon montok sambayangan publik toi ko' karamayan. Otumbayaan yolo do iri nopo nga' kinoyonon montok kinorohingan, om monikid bandar nopo nga' haro kinorohingan poinsoosondii. Imam di noonuan no kasaga'an id zigurat toi ko' bilik id tapak, om kitonggungan yolo montok mantamong do kinorohingan dii om manahak toinsanan kominagan diolo. Imam nopo dii nga tulun Sumerian ii bobos kikuasa om masyarakat do Assyro-Babylonian.

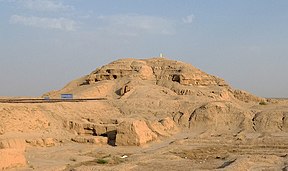

Iso zigurat di atamangan kopio nopo nga' Chogha Zanbil id kabataan do Iran.[8] The Sialk ziggurat, in Kashan, Iran, is one of the oldest known ziggurats, dating to the early 3rd millennium BCE.[9][10] Ziggurat designs ranged from simple bases upon which a temple sat, to marvels of mathematics and construction which spanned several terraced stories and were topped with a temple.

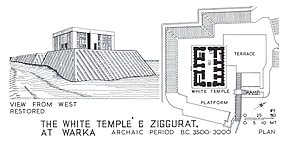

An example of a simple ziggurat is the White Temple of Uruk, in ancient Sumer. The ziggurat itself is the base on which the White Temple is set. Its purpose is to get the temple closer to the heavens,[minog do kisukuon] and provide access from the ground to it via steps. The Mesopotamians believed that these pyramid temples connected heaven and earth. In fact, the ziggurat at Babylon was known as Etemenanki, which means "House of the foundation of heaven and earth" in Sumerian.

The date of its original construction is unknown, with suggested dates ranging from the fourteenth to the ninth century BC, with textual evidence suggesting it existed in the second millennium.[11] Unfortunately, not much of even the base is left of this massive structure, yet archeological findings and historical accounts put this tower at seven multicolored tiers, topped with a temple of exquisite proportions. The temple is thought to have been painted and maintained an indigo color, matching the tops of the tiers. It is known that there were three staircases leading to the temple, two of which (side flanked) were thought to have only ascended half the ziggurat's height.

Pokomoyon om kapansalan

According to Herodotus, at the top of each ziggurat was a shrine, although none of these shrines has survived.[7] One practical function of the ziggurats was a high place on which the priests could escape rising water that annually inundated lowlands and occasionally flooded for hundreds of kilometres, for example, the 1967 flood.[12] Another practical function of the ziggurat was security. Since the shrine was accessible only by way of three stairways,[13] a small number of guards could prevent non-priests from spying on the rituals at the shrine on top of the ziggurat, such as initiation rituals like the Eleusinian mysteries, cooking of sacrificial food and burning of sacrificial animals. Each ziggurat was part of a temple complex that included a courtyard, storage rooms, bathrooms, and living quarters, around which a city spread,[14] as well as a place for the people to worship. It was also a sacred structure.

Pongaruh

The biblical account of the Tower of Babel has been associated by modern scholars to the massive construction undertakings of the ziggurats of Mesopotamia,[15] and in particular to the ziggurat of Etemenanki in Babylon in light of the Tower of Babel Stele[16] describing its restoration by Nebuchadnezzar II.

According to some historians the design of Egyptian pyramids, especially the stepped designs of the oldest pyramids (Pyramid of Zoser at Saqqara, 2600 BCE), may have been an evolution from the ziggurats built in Mesopotamia.[17] Others say the Pyramid of Zoser and the earliest Egyptian pyramids may have been derived locally from the bench-shaped mastaba tomb.[18][19]

The shape of the ziggurat experienced a revival in modern architecture and Brutalist architecture starting in the 1970s. The Al Zaqura Building is a government building situated in Baghdad. It serves the office of the prime minister of Iraq. The Babylon Hotel in Baghdad also is inspired by the ziggurat. The Chet Holifield Federal Building is colloquially known as "the Ziggurat" due to its form. It is a United States government building in Laguna Niguel, California, built between 1968 and 1971. Further examples include The Ziggurat in West Sacramento, California, and the SIS Building in London.

Intangai nogi

Script error: No such module "Wp/dtp/Portal".

Sukuon

Potikan

- ↑ Crüsemann, Nicola; Ess, Margarete van; Hilgert, Markus; Salje, Beate; Potts, Timothy (2019). Uruk: First City of the Ancient World. Getty Publications. p. 325. ISBN 978-1-60606-444-3.

- ↑ "Search Entry". www.assyrianlanguages.org. Linoyog ontok 2020-07-30.

- ↑ "Search Entry". www.assyrianlanguages.org. Linoyog ontok 2020-07-30.

- ↑ "מילון מורפיקס | זקר באנגלית | פירוש זקר בעברית". www.morfix.co.il. Linoyog ontok 2020-07-30.

- ↑ intangai nogi Akkadian zaqru 'popokito, akawas', kopiagal do Hebrew zaqur (זָקוּר) 'popokito, popoingkawas'

- ↑ "The Ziggurat of Ur". British Museum. Linoyog ontok 24 November 2017.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Crawford 1993, p. 73.

- ↑ "Tchogha Zanbil". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Linoyog ontok July 15, 2017.

It is the largest ziggurat outside of Mesopotamia and the best preserved of this type of stepped pyramidal monument.

- ↑ Matthews, R; Nashli, H. F., eds. (2013). The Neolithisation of Iran: the formation of new societies. Oxford: British Association for Near Eastern Archaeology and Oxbow Books. p. 272.

- ↑ Fazeli, H.; Beshkani A.; Markosian A.; Ilkani H.; Young R. L. (2010). "The Neolithic to Chalcolithic Transition in the Qazvin Plain, Iran: Chronology and Subsistence Strategies". Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Iran and Turan (41): 1–17.

- ↑ George, Andrew R. (2007). "The Tower of Babel: Archaeology, history, and cuneiform texts" (PDF). Archiv für Orientforschung. 2005/2006 (51): 75–95.

- ↑ Aramco World Magazine, March–April 1968, pp. 32–33

- ↑ Crawford 1993, p. 75.

- ↑ Oppenheim 1977, pp. 112, 326–328.

- ↑ Harris, Stephen L. (2002). Understanding the Bible. McGraw-Hill. pp. 50–51. ISBN 9780767429160.

- ↑ "MS 2063 - The Schoyen Collection". www.schoyencollection.com. Linoyog ontok 2020-07-30.

- ↑ "The stepped design of the Pyramid of Zoser at Saqqara, the oldest known pyramid along the Nile, suggests that it was borrowed from the Mesopotamian ziggurat concept." in Held, Colbert C. (University of Nebraska) (2018). Middle East Patterns, Student Economy Edition: Places, People, and Politics. Routledge. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-429-96199-1. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Linoyog ontok 17 March 2021.

- ↑ How the Great Pyramid Was Built By Craig B. Smith

- ↑ "The earliest pyramid was the step pyramid of Djoser (2668-2649 BCE) at Saqqara, and was an evolution of the traditional mastaba tomb, a bench-shaped superstructure" in Booth, Charlotte (29 April 2020). How to Survive in Ancient Egypt. Pen and Sword History. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-5267-5352-6.

Toud

- Oppenheim, A. Leo (1977). Ancient Mesopotamia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-63187-7.

- Tillison, Malachi (1993). Sumer and the Sumerians. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-38850-3.

- Crawford, Harriet (1993). Sumer and the Sumerians. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-38850-3.

Pambasaan potilombus

- Black, J.A.; Green, A. "Ziggurat". In Bienkowski, P.; Millard, A. (eds.). Dictionary of the Ancient Near East. London: British Museum. pp. 327–328.

- Beck, Roger B.; Black, Linda; Krieger, Larry S.; Naylor, Phillip C.; Dahia Ibo Shabaka (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. ISBN 0-395-87274-X.

- Busink, T. (1970). "L´origine et évolution de la ziggurat babylonienne". Jaarbericht van het Vooraziatisch-Egyptisch Genootschap Ex Oriente Lux. 21: 91–141.

- Chadwick, R. (November 1992). "Calendars, Ziggurats, and the Stars". The Canadian Society for Mesopotamian Studies Bulletin. Toronto. 24: 7–24.

- Killick, R.G. "Ziggurat". In Turner, J. (ed.). The Dictionary of Art. Vol. 33. New York & London: Macmillan. pp. 675–676.

- Leick, Gwendolyn (2002). Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-026574-0.

- Lenzen, H.J. (1942). Die Entwicklung der Zikurrat von ihren Anfängen bis zur Zeit der III. Dynastie von Ur. Leipzig.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Roaf, M. (1990). Cultural Atlas of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East. New York. pp. 104–107.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Stone, E.C. (1997). "Ziggurat". In Meyers, E.M. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East. Vol. 5. New York & Oxford: Oxford. pp. 390–391.

Popioput soliwan

- UNESCO Heritage site for Choqa Zanbil ziggurat, Iran.

- Article on the status of Sialk ziggurat, Iran.

Template:Wp/dtp/Authority control Template:Wp/dtp/Ancient Mesopotamia topics